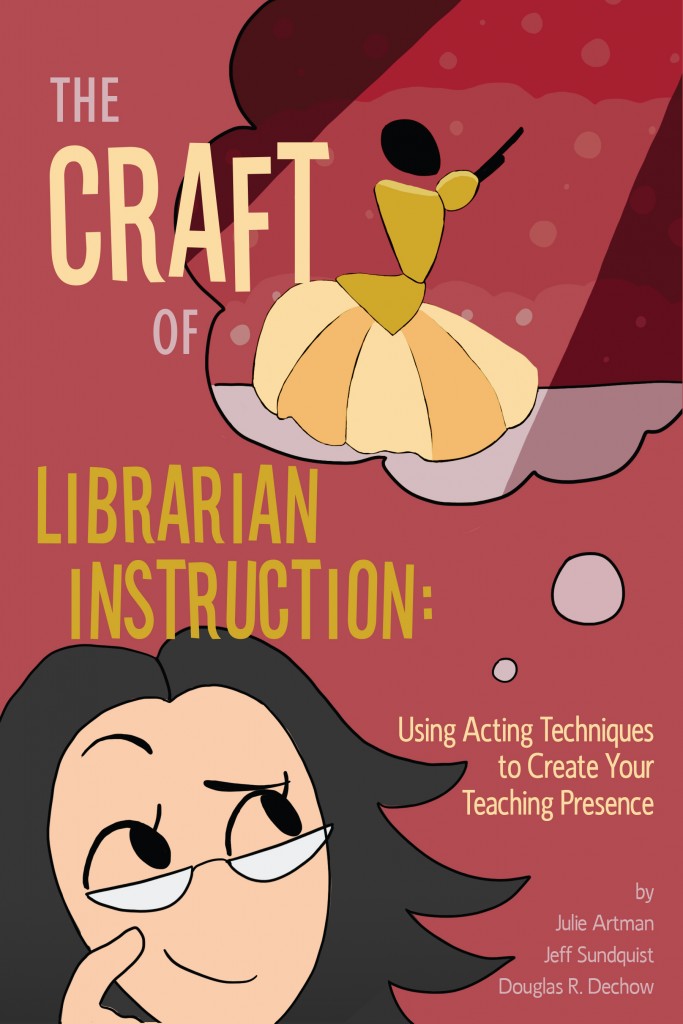

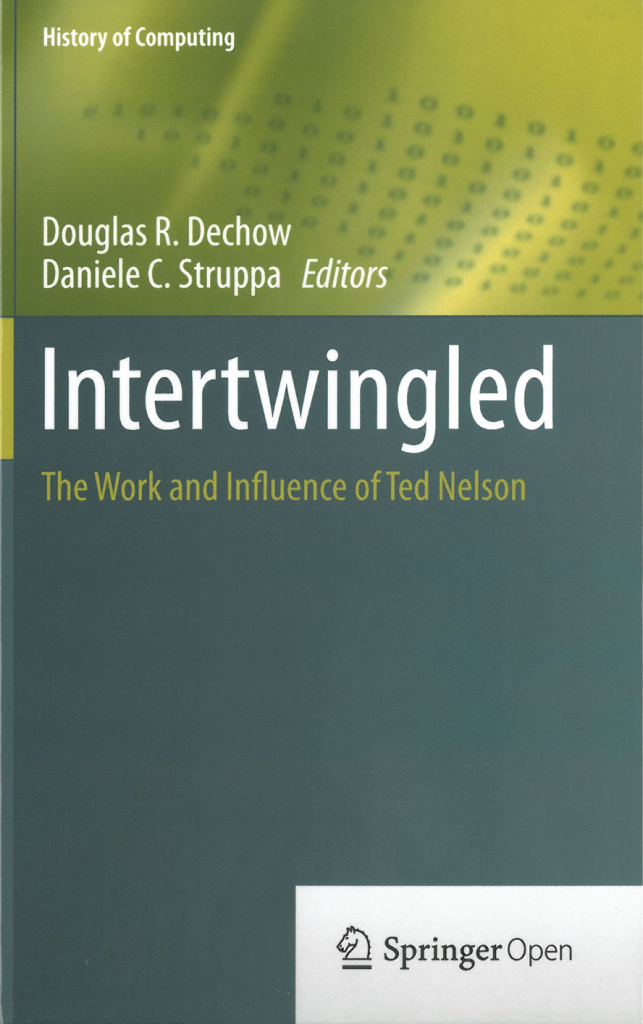

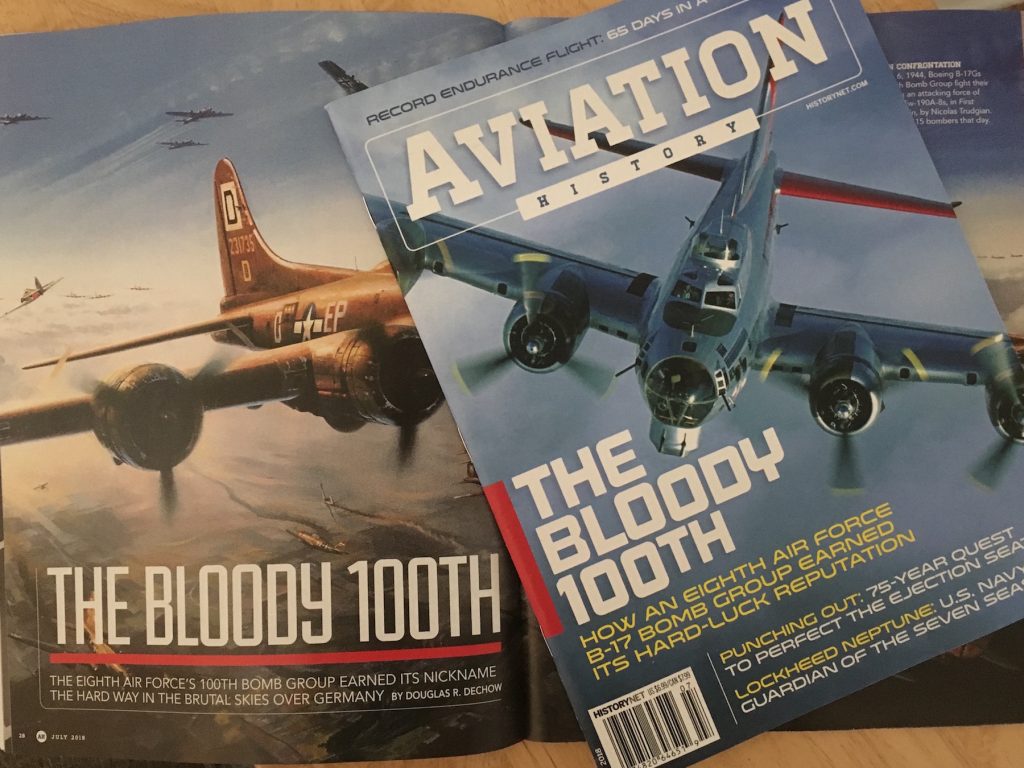

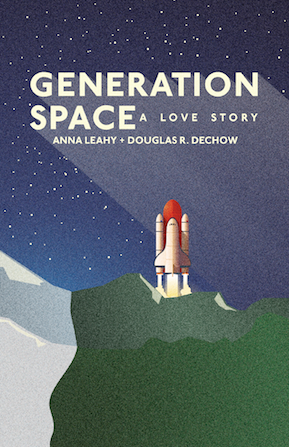

Doug’s article on the 100th Bomb Group was the cover story for the July 2018 issue of Aviation History. He has written about WWII and about aviation for The Atlantic, Air & Space Magazine, LitHub, Fifth Wednesday, Airplane Reading, Curator, the anthology Bombs Away!, and other outlets. He has also published articles and chapters in Creative Writing in the Digital Age, Parade, Poets & Writers, and elsewhere. Doug is the co-author of Generation Space: A Love Story and The Craft of Library Instruction and the co-editor of Intertwingled: The Work and Influence of Ted Nelson.

Doug is the co-author of Generation Space: A Love Story and The Craft of Library Instruction and the co-editor of Intertwingled: The Work and Influence of Ted Nelson.

Doug has talked at libraries and with community groups, has been a featured author at Fall for the Book, and has presented at conferences, including the Association of Writers and Writing Programs conferences. He’s also appeared on radio and television; for a sample, check out his appearance on WGN-TV Midday News.

Residencies at Dorland Mountain Arts Colony, Ragdale, and the Norman Mailer Writers’ Colony have supported his writing.

He is Associate Dean for Library Research and Data Services at Chapman University and lives in Southern California.